"O fearful thought -- a convict soul" Walt Whitman "Captivity is Consciousness -- so's Liberty" Emily Dickinson

The constant buzz of news and speculation about these captive soldiers helped shape the attitudes of all Americans during the years from 1861 to 1865; that period was also, as we know, a productive and stimulating one for both Whitman and Dickinson. Were the stories of prisoners of war, or the controversies about them, anything more than a steady hum in the background of their creativity? Did the Civil War alter their ways of imagining the world--both in terms of the stories of human suffering and cruelty it brought, and in terms of the disturbing visual images that came to illustrate the war news? More broadly, how do writers--then and now-- make use of the idea of captivity and liberation? What does a writer gain from imagining the self "shut up" like a prisoner in an enclosed space? On these pages, you'll find a brief overview of the history of Civil War prisons and prisoners, including period accounts of those prisons that Whitman, Dickinson, and their families would have been likely to read, and engravings and photographs they might have seen. This background, we hope, will stimulate your thinking about confinement and creativity, isolation and expansion, in the poetic context. You'll also find information about Whitman's experience of the War, including his anxiety during the captivity and imprisonment of his soldier brother George, linked to poems and prose writings that are concerned with similar themes. Although Dickinson's contact with war prisoners was less immediate than Whitman's, her poems are shot through with references to enclosure and confinement, as she teaches herself (and her readers) to see big things in small spaces.

|

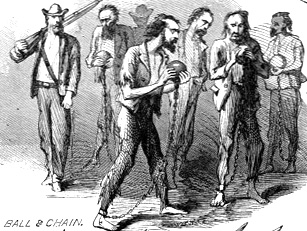

More than 400,000 of the soldiers who fought in the Civil War would eventually

find themselves captured by the opposing side: the Union and the Confederacy

lodged prisoners of war in over 200 different locations. For many, being

sent to an infamous prison camp like the ones at Andersonville, Georgia

or Elmira, New York was to be feared nearly as much as death in battle.

Some found captivity the worse fate, particularly toward the end of the

War as food and supplies dwindled: the conditions of scarcity that made

life difficult enough for the troops in the field were even more inhuman

for prisoners in the stockade. As sensationalized accounts of the camps

trickled out to the public, the treatment of prisoners became a cause for

outcry on both sides, with Northerners and Southerners alike accusing each

other of neglect and worse atrocities.

More than 400,000 of the soldiers who fought in the Civil War would eventually

find themselves captured by the opposing side: the Union and the Confederacy

lodged prisoners of war in over 200 different locations. For many, being

sent to an infamous prison camp like the ones at Andersonville, Georgia

or Elmira, New York was to be feared nearly as much as death in battle.

Some found captivity the worse fate, particularly toward the end of the

War as food and supplies dwindled: the conditions of scarcity that made

life difficult enough for the troops in the field were even more inhuman

for prisoners in the stockade. As sensationalized accounts of the camps

trickled out to the public, the treatment of prisoners became a cause for

outcry on both sides, with Northerners and Southerners alike accusing each

other of neglect and worse atrocities.