ON IMPRISONMENT AND WHITMAN'S POEMS:

-

Read the surrounding parts of the excerpts

given here about prisoners from the 1855 version of "Song of Myself." In

what other ways does the speaker advocate liberation? Compare the

passages on prisoners to the passages about other "problematic" citizens

of his United States-- drunkards, prostitutes, corrupt politicians-- and

think about how he proposes to integrate them into his utopian vision of

the Union. Or: compare the way he discusses liberating prisoners with the

way he discusses freeing the

runaway slave.

-

Read the whole of "The Sleepers" (in different

editions, if you wish). Departing from the two excerpts from the beginning

and end of the poem given here, think about what happens in the course

of the poem to bring about the change in attitude. Do you read this poem

as an internal monologue, or are there other voices and conflicting visions

that must be resolved? Is the "resolution," in your reading, a successful

one?

-

Read some reviews

of Whitman's war poetry, and critique the critics. Refer back to some

of the specific poems from Drum-Taps they mention, and establish

your own interpretation.

-

Read the postwar poem, "The

Singer in the Prison." What is its attitude toward imprisonment and

prisoners? In what ways is that attitude more conventional than the ones

demonstrated in the earlier poems, and what do you make of the change?

Stylistically, how is the interpellated song (the hymn the female singer

performs) "like" or "unlike" other Whitman poems? Given that he often referred

to Leaves as his "song," do you sense any affinity between Whitman's

poetic self and the singer here? What would that suggest about his relationship

to his audience?

ON IMPRISONMENT AND DICKINSON'S POEMS:

-

Read the various scholarly assessments

provided of "They shut me up in Prose." On what

points do these readings differ? Are there disagreements about the most

significant meaning of each individual word, or does it seem that each

critic is simply putting a different "spin" on it? Can you detect the vision

of Dickinson-- the person and the poet-- that the critic is trying to create?

Now turn your attention to the poem itself, and particularly to the most

ambiguous and problematic parts: what does "still" mean; what roles to

"they" and "himself" play; what does "easy as a Star" mean? After creating

this reading, is "your Dickinson" different from the critics'?

-

Using the manuscript facsimiles provided,

make your own "edition" of one of the poems here. Pay attention to punctuation,

and to the stress on individual lines and words. How does Dickinson use

the physical space of the page? Does her use of space suggest anything

to you about the content of that particular poem?

-

Read the versions of "A

prison gets to be a friend." Does the rest of the poem support the

little homily with which it begins? What do you make of some of the cryptic

references in the middle stanzas-- the "Planks," "plashing in the Pools,"

the "demurer Circuit," the "Cheek of Liberty"?

-

In "Dying! To be afraid

of thee," Dickinson sets up an analogy between stricken soldiers together

in a battle and the progress of love. Whitman, too, spoke of fighting and

comradely love (Dickinson says "Friend," then "Love"-- an interesting move

to discuss in itself) together in his war writings. How do the two treatments

differ?

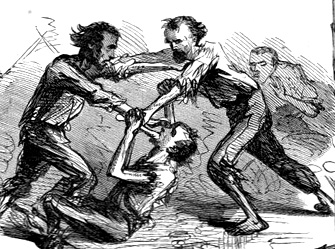

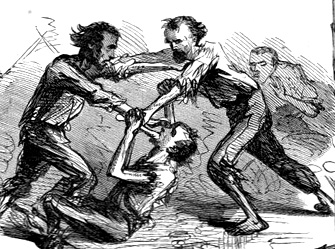

ON IMPRISONMENT AND NINETEENTH-CENTURY LITERATURE AND CULTURE IN THE U.S.:

-

Research other, more conventional writers

of the period who wrote about captivity (think of the religious aspect

as well as concrete historical influences like slavery). How broadly do

they encourage us to think about the meaning of liberty and human freedom?

Compare to one of the Whitman or Dickinson poems here.

-

Using the bibliography

and links provided here, research other poems from the Civil War period

from lesser-known writers. Are there common images, phrases, or stylistic

"moves" among these poems? Is the voice of the speaker like or unlike that

in a given Whitman or Dickinson poem? Does it claim direct contact with

the experiences described, or does it render those experiences abstract--

and if so, why? You might look at the

site on Civil War elegy for ideas about fitting some of these

works into a longer generic tradition.

EXPANDING TO OTHER TOPICS:

-

Follow one of the historiographical controversies

about the War mentioned here: for instance, the debate over whether Grant

was right to end the prisoner exchanges; whether Northern or Southern prison

camps were maliciously administered; or the divisive Wirz trial. Think

about the way that these events require interpretation as well as

the dissemination of factual information, and what passions and values

one might bring to such interpretation. How are the interpretive processes

we bring to history similar to the process of analyzing the "story" of

a writer's life, or the "meaning" of a poem? (You might want to refer to

some of the competing critical statements about the Whitman and Dickinson

poems provided above.)

-

Research the 20th-century

poetry of testimony, which is often impelled by a traumatic experience

of war or unjust imprisonment. Where do you "see" the trauma of such large

historical events leaving its trace on these writings? In light of later

poets, how "modern" do 19th-century texts about the traumas of the Civil

War seem?

-

Research prison literature, from Boethius

to Malcolm X, and think about how these writers weave the experience of

incarceration into their work. Or look at some of the on-line 'zines and

other productions of contemporary prisoners. Consider style as well

as content: does language become as bare and stripped-down as a jail cell?

Or does the imagination become florid, multiplying to fill up the empty

space? How does prison concentrate (or break) the speaker or narrator's

sense of self?

|