|

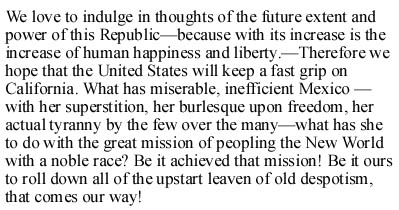

In an editorial in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of May 11, 1846, justifying the Mexican War, Whitman writes:

"Spirit" here marks the interfusion of the physical with the spiritual--something breath (as divine "inspiration," for example) also suggests. But here the nation’s will to "expand" is also the mirror image of the Poet’s version, bearing not simply the power to resuscitate the dying, but also to "crush" opposition to a resistless will. Passages like this one help us to see how Whitman’s "Poet" in its earliest figurations is steeped in contemporaneous discourses associated with the nation’s unfolding rhetorics (and practices) of manifest destiny. From an editorial in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle entitled "Annexation," June 6, 1846:

Here "our eagle" represents at once the United States and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in which this editorial is printed. Thus the Poet’s and the Nation’s manifest destinies align. Once one begins to think this way, to place dilation and all its coincident meanings at the center of a whole range of connections between dilation, inspiration, and conspiracy, then the "breathing" seems literally everywhere. As Whitman says in the same editorial:

Less and more, what Whitman-the-Editor working at the Brooklyn Daily Eagle wants done to Mexico and the Mexican people is a variation of the emboldening, the inspiring, the clutching, and the dilation that are part and parcel of the work of his Poet-Nurse-Soldier (Source: Hunt Howell, Northwestern University).

|